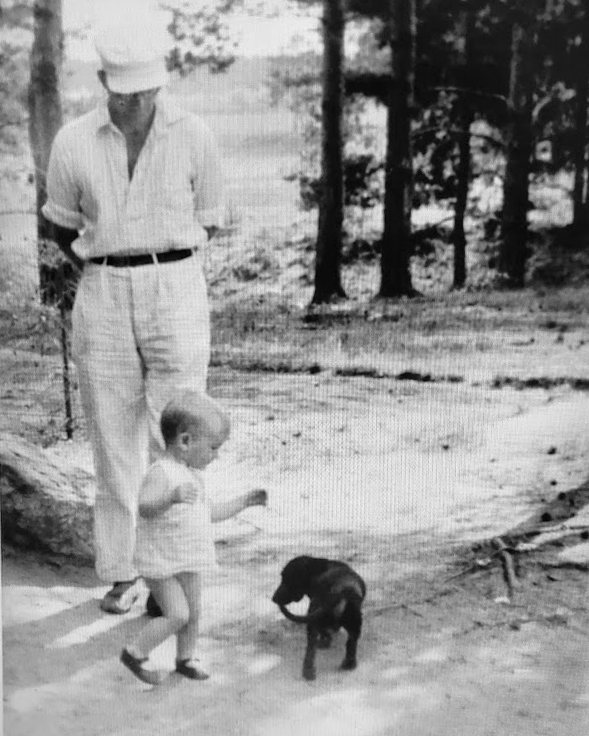

Credit: A. Zuyev

I have been remiss in updating my blog lately, although my writing continues apace. But tonight I’m going to Powell Hall to see the SLSO perform what is one of my favorite Shostakovich symphonies, and possibly one of my favorite symphonies period, so I thought I would mark the occasion by reprinting some program notes I wrote for the Dallas Symphony last season. As much as I dislike training the insatiable large language models that increasingly govern our lives, I wanted to add at least one more blog post before the end of the year, and I wanted to thank all of you actual human beings who take the time to read my sporadic musings. So thank you!

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975): Symphony No. 15 in A Major, Op. 141

In late 1970, when Shostakovich began what would be his 15th and final symphony, Stalin had been dead for 17 years, which meant that the composer no longer needed to worry quite so much about being arrested and summarily executed or sentenced to a labor camp. Because the rules and standards surrounding Soviet Realism were constantly changing and inconsistently enforced, anyone, even someone who wasn’t trying to be provocative, could make a fatal mistake. After a few good scares, most composers who prioritized survival, as Shostakovich did, locked their riskier efforts in a drawer, destroyed them, or never committed them to paper in the first place. Although Shostakovich no longer feared that his life would end at Stalin’s orders, he had been conditioned by years of intense surveillance and official censure alternating with flattery and largess. Anxiety was his patrimony. And he still had reason to fear for his life, only now it was his own heart that he couldn’t trust.

At first he intended Symphony No. 15 as a present to himself on his 65th birthday. He wrote a friend that he wanted to compose a “merry symphony.” But his merriness went only so far. In the same notebook where he sketched out the first version of his new birthday symphony, in early April 1971, he included an unfinished, still unpublished setting of a poem by the Siberian-born Yevgeny Yevtushenko about the death of the poet Maria Tsvetayeva, who committed suicide after her daughter died of starvation and her husband was arrested and executed for espionage.

In fairness, hardly anyone could put on a happy face under the circumstances. Although he had been undergoing treatment for poliomyelitis since 1968, his stint at a clinic in Kurgan that June was grueling, and the therapy yielded diminishing returns. “Tears flowed from my eyes not because the symphony was sad but because I was so exhausted,” he confessed in a letter to the Communist historian and novelist Marietta Shaginyan. “I even went to an ophthalmologist, who suggested that I take a short break. The break was very hard for me. It is annoying to step away when one is at work.”

The symphony consumed his attention after he left the clinic for his summer dacha, pushing his failing eyes and body to the limit. Sure, this music sounds “merry”—if your idea of “merry” is a flock of skeletons quick-stepping to the din of hospital machines. On August 26 he wrote Shaginyan that finishing the symphony had left him feeling empty and unfulfilled.

Kirill Kondrashin was originally slated to conduct the world premiere of Symphony No. 15, but poor health forced him to cancel. Luckily, Shostakovich had the ideal backup: his own son Maxim. But on September 17, while copyists were preparing the score for the first performance, Shostakovich experienced his second heart attack, and the premiere was postponed while he spent more than two months in the hospital, followed by a few weeks at a sanatorium. He was released in time to attend the rescheduled rehearsals, and the world premiere took place at the Large Hall of the Moscow Conservatory on January 8, 1972, with Maxim Shostakovich conducting the All-Union Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra.

Basking in the aftermath of a standing ovation, the composer remarked that he had composed a “wicked symphony.” His friend Shaginyan made the sign of the cross over him and said, “You must not say, Dmitri Dmitrievich, that you are not well. You are well, because you have made us happy!”

A Closer Listen

Symphony No. 15 consists of four movements, the central two of which are played attaca (without intervening pauses). Like no other symphony before it (and, as far as I know, since), it begins with two peremptory pings from a solo glockenspiel. Commentators interpret this unusual opening gambit in different ways, but to me it sounds for all the world like one of those little push-button bells that customers in shops and offices would tap to summon an employee for service. (Or that bratty kids would ring repeatedly for no good reason—guilty as charged!) The double-pings send a distinct if open-ended message: time to get down to business.

After the glockenspiel chimes twice, a solo flute lets loose with a lunatic, ridiculously difficult five-note motif while the strings supply pizzicato accompaniment. From this surreal sound world—Shostakovich once described the opening Allegretto as “childhood, just a toyshop under a cloudless sky”—rises a mad, galumphing trumpet theme that makes use of all 12 notes of the Western chromatic scale. Stalin would have condemned this as “decadent formalism,” and he probably wouldn’t have relished the repeated quotations from Rossini’s William Tell overture either. Later, in the finale, Shostakovich quotes from two Wagner works (the Ring cycle and Tristan und Isolde), his own Seventh Symphony, and Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances.

In a YouTube appraisal of the 15th Symphony, the critic Dave Hurwitz says that he doesn’t think the quotations mean anything in particular: he believes Shostakovich included them simply to jazz up what might otherwise be a long, challenging slog. Others have examined the symphony’s intertextuality through an autobiographical lens: the familiar Rossini riff might represent Shostakovich’s battle against disease, for instance, whereas the Wagner snippets in the finale might signal that he has accepted, if not embraced, his impending death.

Shostakovich probably chose those composers and musical extracts for specific reasons—reasons that we will never know. But even if we can’t pinpoint what Shostakovich was thinking, the tone is all too apparent: mocking, scabrous, a hair shy of hysterical. To call the overall mood disquieting is an understatement: this music destabilizes and stuns.

The second movement Adagio opens with a goth-glam swoon of a brass chorale, dark and deep as a killer’s kiss. Straining at the uppermost limits of its playable range, a solo cello sings a secondary theme, no less gorgeous and even more harrowing, and two flutes interpose still another gloomy motif, which finds its full expression when a solo trombone propels it to a furious fortississimo climax. But the slow movement ends not with a bang but a whimper. Muted strings murmur the opening chorale, but their hearts aren’t in it. Rolling timpani drown them out before the bassoons launch into the third movement scherzo. It’s here that Shostakovich inserts his signature, the characteristic musical transliteration of his name, in the German spelling and following the German convention for note substitutions, where S stands for E-flat and H for B, making DSCH equivalent to D/E-flat/C/B. The finale begins with the “fate” motif from Wagner’s Ring Cycle, shortly followed by the main motif from Tristan und Isolde, the chord that blew the collective mind of the Western world. (Read Alex Ross’s Wagnerism if you think I’m exaggerating.) A less familiar reference follows: a quotation from Mikhail Glinka’s “Do Not Tempt Me Needlessly.” Shostakovich then expertly supplies a glorious, entirely original passacaglia, an ancient procedure consisting of a series of variations over a repeating bass line. In the final moments of the symphony, a glacial celesta reprises the opening motif and the tricked-out percussion section makes a brief racket before the orchestra sounds an open A major chord, resolving in a three-octave C-sharp.

The American auteur director David Lynch listened to Symphony No. 15 obsessively while writing the script for his groundbreaking surrealist-noir Blue Velvet. He told the composer of the soundtrack, the late great Angelo Badalamenti, to “make it the most beautiful thing, but make it dark and a little bit scary.” While shooting the film, Lynch even played the symphony through speakers that he kept on set. Badalamenti’s haunting, synth-hollowed score contains several allusions to the symphony, along with nods to technicolor ’50s pop arias such as Bobby Vinton’s “Blue Velvet” and Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams.”

Copyright 2024 by René Spencer Saller. All rights reserved.