Just to get this out of the way first, I had some trepidations when I started this biography. As a native St. Louisan, I feel reflexively defensive about Chuck Berry and his complicated legacy, which in many ways mirrors the city that spawned him (us). As with most native St. Louisans, there aren’t too many degrees of separation between us. Decades before I got to interview Chuck Berry in person, I heard story after story from people who met him or knew him or had minor dealings with him. My own mom, a public schoolteacher who moonlighted as a waitress for extra money, served him and one of his very young blond dates on a couple of occasions. She said he was polite and friendly and a good tipper. A perfect gentleman–who was fucking an apparent teenager.

Berry is definitely the most charismatic person I have ever met and probably the most significant person I have ever interviewed, and I didn’t get much time with him–maybe 20 minutes or a half-hour, and I wasn’t allowed to use a tape recorder, which both amused and irritated me, since I’m a stickler for quoting people precisely, and, to put it mildly, Chuck Berry resists paraphrase. He had the most peculiar and poetic way of phrasing things, a sort of ur-Country Grammar lexicon that is impossible to replicate. Some of his gnomic locutions reminded me of my late grandmother’s sayings; others seemed unique to him. After our interview, I literally ran to my office and transcribed my notes right away, so I would be able to capture as much of that sui generis voice as possible. I could still hear his voice ringing like a bell in my brain, and I could still feel the grasp of his enormous hand, the force of his singular star power. Most celebrities (especially septuagenarian celebrities, as he was at the time) seem smaller and more ordinary in real life. Not Chuck Berry, though: even eating chicken wings in a goofy captain’s cap, he was majestic, mysterious, suffused with dark energy disguised as mere genius.

I knew before I started Smith’s comprehensive and unstintingly honest but enormously sympathetic biography that his would need to be an unauthorized biography. Berry was protective of his privacy and his legacy, and his family no doubt feels that Berry’s own biography is definitive. But as fantastic as Berry’s autobiography is (for one thing, it replicates his voice exactly, which makes sense since he actually wrote it), it conceals as much or more than it reveals. This is going to sound like a strange comparison, but in many ways Smith’s great challenge is similar to the one faced by Jan Swafford in writing about Johannes Brahms, another genius perv who wore mask over mask over mask and drenched every meaningful extramusical statement in irony. With a subject as complex and contradictory as Berry or Brahms, how can the biographer tell if you have found his “true” self and not another mask? More likely the “true” self is this multitudinous assemblage of lies, myths, delusions, and unconscious compulsions, but it takes a biographer as talented as Swafford or Smith to present the subject in all its irreducible complexity. It helps that they’re both very good at writing about music qua music, which is, after all, the language Berry and Brahms spoke best.

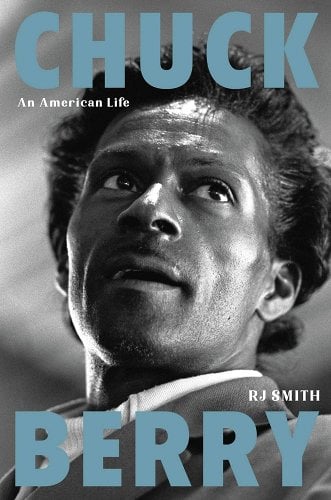

Despite my pledge to use the library rather than buy more books, I ended up ordering a copy of Chuck Berry: An American Life after I finished the library book. I don’t write about pop music anymore, so I won’t use this as a research source the way I refer to my Swafford bios or my music encyclopedias, but I want to have this in my collection, and I want to be able to press it into the hands of the next blowhard fool who says something ignorant and dismissive about the man who gave my city, nation, and world so many priceless gifts.

In the event that anyone wants to read my short interview with Berry, I cut-and-pasted it below, since it’s old enough to be getting unsearchable, at least in the existing RFT archives:

Riverfront Times, October 17, 2001

Somewhere around the middle of the long, long list of things that make Radar Station sad, somewhere between kitten torture and the demise of the bustle in ladies’ skirt fashions, is the fact that St. Louis rock icon Chuck Berry doesn’t get the respect he deserves in his own hometown. Sure, he’s got a bronze star on Delmar, his monthly gigs at the Blueberry Hill Duck Room always sell out, and Gov. Bob Holden and Mayor Francis Slay are scheduled to present him with “proclamations of his greatness” at his big birthday bash at the Pageant on Oct. 18. These honors notwithstanding, when your garden-variety St. Louis hipster utters Berry’s name, it’s likely to lead to a crack about coprophilia and underage girls, not a serious discussion about his astonishing musical legacy.

It’s partly his own fault. Anyone who’s seen Berry in concert recently is painfully aware that he phones in his performances more often than not, seldom bothering to rehearse with his pickup bands or even tune his guitar. No one held a gun to his head when he outfitted his employee bathrooms with hidden video cameras. No one forced him to record the staggeringly stupid novelty jingle “My Ding-a-Ling.” But what does it say about the kitten-torturing, bustle-slighting world we live in that this infantile paean to Berry’s illustrious pee-pee remains his all-time biggest hit, bigger than “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Little Queenie,” “Maybellene,” “Nadine (Is It You?)” and “No Particular Place to Go”? What does it say about us that we’d rather make poop jokes than talk about the poetic brilliance of lyrics such as “with hurry-home drops on her cheeks” or “as I was motorvatin’ over the hill” or “campaign-shouting like a Southern diplomat”? Indeed, we’re mindless sheep, too busy playing with our own ding-a-lings to appreciate the legend who duck-walks among us.

In the end, of course, it doesn’t matter whether we make dumb gibes or issue proclamations. Berry’s legacy is right there on his records: those slithery, wild, scabrous guitar licks; those groin-grinding jump rhythms, that heady elixir of honky-tonk and R&B — the very essence of rock & roll, in all of its primitive, spastic, id-centered glory. Without Berry’s quicksilver genius, rock music as we know it would not, could not exist.

Radar Station had the singular pleasure of interviewing the brown-eyed handsome man in person last week, when he met with us at Blueberry Hill. At nearly three-quarters of a century, Berry looks dapper and alert. Wearing a black windbreaker and his signature captain’s hat, he sits at the head of the table, in front of an uneaten basket of hot wings and a glass of what looks like orange juice. He urges us to move closer — not because he’s trying to get fresh with us but because he’s a little hard of hearing. Radar Station (who suddenly feels too cute to be 9,460,800 minutes over 17) finds his gallantry irresistible, if absurd. He fixes his cloudy black eyes on our face and, when asked how he’d like to be remembered, politely informs us that he doesn’t care. “People’s opinions can’t be altered,” he observes cheerfully. “Realizing this, I’ve found much pleasure and peace.” Asked to name his favorite song, he says, “It’s just like kids — how can you say you love your boy more than your girl, your angel more than your brat?”

Berry doesn’t seem to mind being interviewed, but he doesn’t like to indulge in freeform reminiscence: “A guy came in, some college student. He set down a hand tape-recorder, and he said, ‘Chuck, I’ve been waiting for this moment for six years. Go ahead and talk.’ I said, ‘Well, then, we’re done now. You ask the questions — I’ll answer anything you ask, but I’m not just going to talk. You can even ask me what kind of underclothes I’m wearing, and I’ll tell you.'” Radar Station, a helpless literalist, takes the bait and asks him. “Good ones,” he responds with a wide, sly grin. “Briefs today, but I own a variety.”

Having established this important information, we ask whether he has any comment on the lawsuit his longtime pianist Johnnie Johnson filed recently, wherein Johnson claims that he deserves co-writing credit on most of Berry’s classic songs. “It’s not Johnnie that’s doing this,” Berry says sadly. “I’ve known him 40 years. Someone inspired him to go along with him and seek their desire to try for an easy dollar. At the Pageant’s grand opening, I talked to him for 20 minutes in the dressing room. At that time, I didn’t know [about the lawsuit]. If I would have known, I would have popped the question: ‘Hey, baby! What’s up with that?’ But he never said a mumbling word.”

Berry, who intends to keep rocking for the next 20 years, isn’t holding grudges. Besides playing out regularly, he’s recording a new album, which has been on the back burner since 1978. He claims he’s written nine new songs, but he doesn’t want to estimate a release date. “I thought last March, but I might as well not predict anymore. It will take the application of time, will and effort,” he says. Berry’s daughter and son, among others, will probably back him up. “I have to let them do something, or else I’ll pay family dues,” he cackles. “Even Keith Richards or Johnnie Johnson — I’d welcome them if they wanted to play. A lot of people would be surprised. All I want is a good song.”

Chuck Berry celebrates his 75th birthday on Thursday, Oct. 18, at the Pageant, with special guest Little Richard.