When I was almost five, before I started kindergarten, my parents moved us from their student-housing apartment at Spring and Delor, in South St. Louis, to an old ramshackle stucco house on Bompart, in Webster Groves. I don’t remember how I met Lisa, but we were the same age and lived nearby (less than a minute away if we ran through the Gibsons’ yard, which we always did), and so we became best friends. I admired her beauty and athleticism, her exotic Catholic customs–preparing for First Communion in her frilly little bride’s dress, reciting the rosary, enumerating the various features of Hell–and her ability to make friends and not come off as unforgivably weird, which is eventually what caused our friendship to founder, in the tween years, when the chasm between the popular and the unpopular widens with the onslaught of hormones.

When Lisa was in her early teens, her mother died–her mother had been very loving, the kind of woman who would take you in her arms and hold you when you are sobbing in terror and shame–and unfortunately, her father behaved the way too many dads behaved back then. I remember him as an ambulatory Bad Mood, a sudden stink of cigar and angry sweat, a basement bellow. I was terrified of him, but unlike Lisa I could always run home when he started shouting. Once when we were seven or eight, Lisa cried out in tears to me from her second-floor bedroom window, begging me to come back inside to play, assuring me that he didn’t mean it and wasn’t really that mad. I had run out of her house after her dad had screamed at us, and even though I never stopped feeling sorry for her and ashamed of myself, I was more scared of him, so I barely even hesitated: I just ran home. Her dad’s threats always struck me as credible. My dad was human, which is to say imperfect, but he was kind, especially to children and animals; he wasn’t violent, and he seldom raised his voice. My grandpa was similarly gentle. I wasn’t used to volatile men, and I couldn’t have protected Lisa even if I had been brave enough to try. But I still wish I had tried. I wish I had been braver, a more loving friend.

No one needed to stand up for her when her mom was alive. Her mom constantly appeased her dad while also lavishing love on her many kids. Lisa was the seventh of seven kids, which was common back then, when birth control was legal but still a grievous sin for good Catholics. I always thought Lisa was her mom’s favorite, but it’s possible that all her siblings felt that they were Mrs. Jackson’s favorites. Even after she became ill with emphysema, she had endless energy for mothering. She was as talented at love as her husband was bad at it.

Lisa and I fell out of touch a few years before her mom died, and I saw her maybe once when we were young adults, in our early 20s. She was surprisingly tall, even though she had been short for her age as a kid, shorter than me anyway. We were at a loud and crowded Painkillers show, at the Great Grizzly Bear in Soulard, so we didn’t have much time to chat, but I remember being happy that she had made it through somehow, that she had survived her childhood and the unthinkable loss of her mom. We reconnected on Facebook a couple of decades after that, but unfortunately that was the same year she died, not long before what would have been her 47th birthday; we never got the chance to see each other again in real life, even though she lived a few neighborhoods over, perhaps a five-minute drive away. I cherish our few Facebook messages, as I do my many memories of her. I know she must have been a superb mother, and it breaks my heart that her only, much-loved daughter lost her at about the same age that Lisa was when she lost her own mother. (I’m consoled by the knowledge that Lisa chose a man who was the opposite of her dad, a good and loving father.)

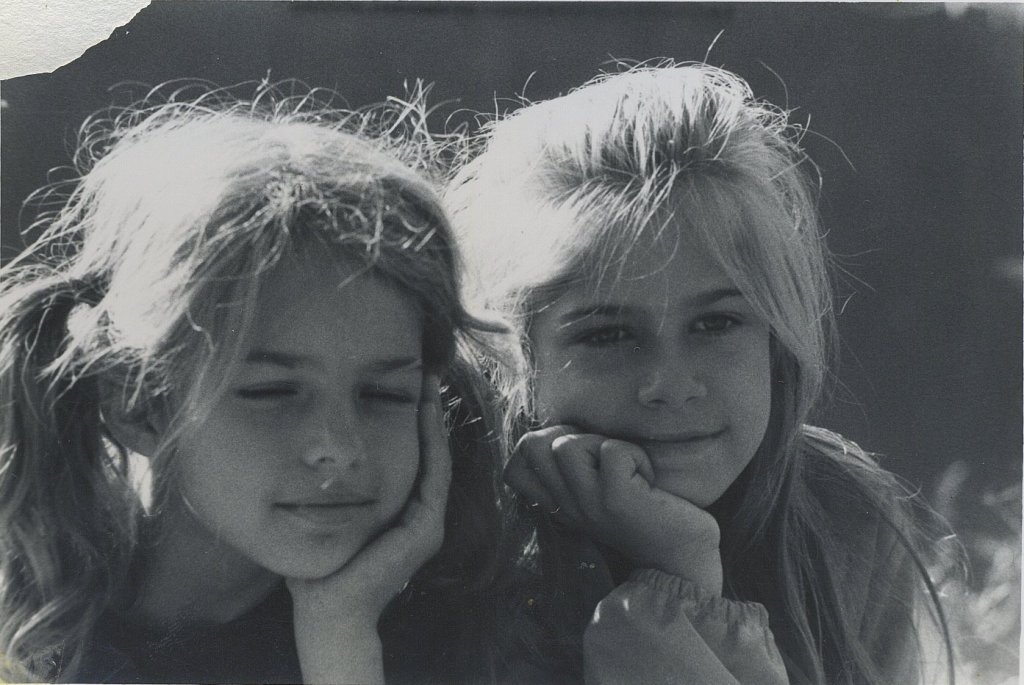

I prefer to dwell on the happy memories of Lisa. Her abundant beauty: she could have been a child model, with her shining flaxen hair and her honest blue eyes. Although she didn’t share my love of lazing around all day reading from her mom’s old box of Nancy Drew mysteries, the ones with the tweedy blue covers from the 1940s, she was a cheerful participant in most of my idiot schemes and projects, and I hope I returned the favor. We devised inscrutable choreography to “Hit the Road, Jack” and “Maxwell Silver Hammer” and made squirrel costumes out of my mom’s old nylons. We sold her dead grandfather’s wide silk ties on the street to skeptical pedestrians and Webster College students, and then cut up the rest to make Barbie attire. We bought a frozen chocolate-cream pie at the grocery store with coins we had scrounged from various couch and sofa cushions, and then ate the entire thing, semi-thawed, in her basement before getting violently ill. We caught a praying mantis and named him Hermie, a compromise name because one of us thought Herman would be better, and the other thought Herbie would be better, and I no longer remember who preferred which name because we both had equally dumb reasons for our choices, related to the cinematic sentient VW Bug and the patriarch of the Munsters. We caught a few cockroaches in my old dilapidated house’s upstairs bathroom and fed them to Hermie, feeling brave and resourceful. I don’t remember what happened to Hermie, but I hope he escaped our ministrations somehow. We were fine with our dogs, cats, guinea pigs, and rodents, but we didn’t know the first thing about mantids.

No one has ever asked me to name my favorite Taylor Swift song, but if asked (and apparently even if unasked) I would not hesitate to say “seven,” from folklore, which, as cornball as this sounds, gave me chills of recognition the first time I heard it and sometimes still does. It sounds like my memories of Lisa: a foundational friendship that was entirely based on proximity and coincidence and yet also perfect for a time. Under duress, I could probably come up with some semipersuasive blah-blah-blah about Swift’s subtle enjambment, or the way the verse melody veers off into slight variations that almost make it sound through-composed, instead of the supposed “folk song” it supposedly is. But I would be lying if I said I loved the song for those peripheral tricks instead of my real reason, which is that it makes me think of Lisa, who died years before “seven” was written.

Back in 2013, when we briefly reconnected, I told Lisa that I still remembered her birthday every year, which is unusual for me, someone who seldom remembers dates or numbers in general. She instantly shot back a message with my correct birthday.

Passed down like folk songs, the love lasts so long. (This time I tried to embed the video, but YouTube wouldn’t let me. So you will have to click on the link if you want to hear this Taylor Swift song, sorry.)