As much as I would prefer to pretend that a good four months hasn’t elapsed since my last blog update, I feel obliged to attempt some kind of explanation. The truth, sadly, is that I have been very lazy and didn’t feel like it. Instead of blogging, I have been doing my best to keep up with my freelance work while indulging my fitful enthusiasms, which range from French perfume to Chappell Roan to the Dolly Parton crazy quilt I started a few months ago in a kind of aspirational delirium. I began the crazy quilt as a coping mechanism because I was having nightmares about the news and felt a conflicting need to stay informed. Essentially, my one crazy trick is that I work on my Dolly quilt while I listen to my embummening world-news programs. I peer at my crooked stitches instead of the endless footage of starving babies, burned and mutilated children, flattened neighborhoods, and inconceivable civilian carnage. I can’t swear my technique is morally defensible, but it’s allowing me to stay informed without going entirely insane. I would describe my primitive needlework as a form of meditation, only with supplementary blood and cursing. If it’s not quite a thought preventer, it’s also not a thought promoter.

I might have continued lolling indefinitely on my reliable dilettante setting, but I feel strongly compelled to evangelize on an unrelated topic, one that’s more interesting than my lamentable work habits, and that is the pipe organ. More precisely, I would like to recommend one of my favorite ways to learn more about it: the superb weekly radio program The King of Instruments. I’ll get around to reviewing this treasured resource soon, I promise, but in the meantime, click on that hyperlink, choose any episode from the show website’s clearly organized archives, and listen for yourself. Do yourself a favor and listen through some decent speakers or headphones, not your dogshit built-in phone or laptop speakers. The best argument in favor of pipe organ music is always going to be listening to it.

The pipe organ is a difficult instrument to master, but it’s also difficult to understand if you’re not an organist, which is true of myself as well as almost everyone else on this planet. It’s a gigantic, implausible, Rube Goldberg–like contraption that transforms a building’s architecture into an enormous amplifier and speaker to transmit the baddest-ass sounds you’ve ever registered in your actual ass (those wooden church pews are startlingly good conductors). If you tried to describe the instrument to someone who had never seen or heard of one, they might imagine something out of David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ, or maybe a sentient gargoyle-ghost who speaks through the walls and makes your spine and molars vibrate with his godlike basso profundo. What other instrument can be felt in the body—not just in the organist’s body but in the bodies of all the audience members, all those inside the uncanny musical valley carved out by the pipe organ? As a teenager I used to attend punishingly loud punk-rock concerts, made possible by towering stacks of crackling Marshalls—I’m lucky, undeservedly so, that my hearing remains intact—but the loudness of a pipe organ is altogether different from the Ramonesian, feedback-blasting-out-my-ears-makes-me-so-high kind of loudness that I craved from age 14 to 17 or so. Even at its shrillest or most stentorian, the pipe organ doesn’t hurt your ears so much as rattle your bones.

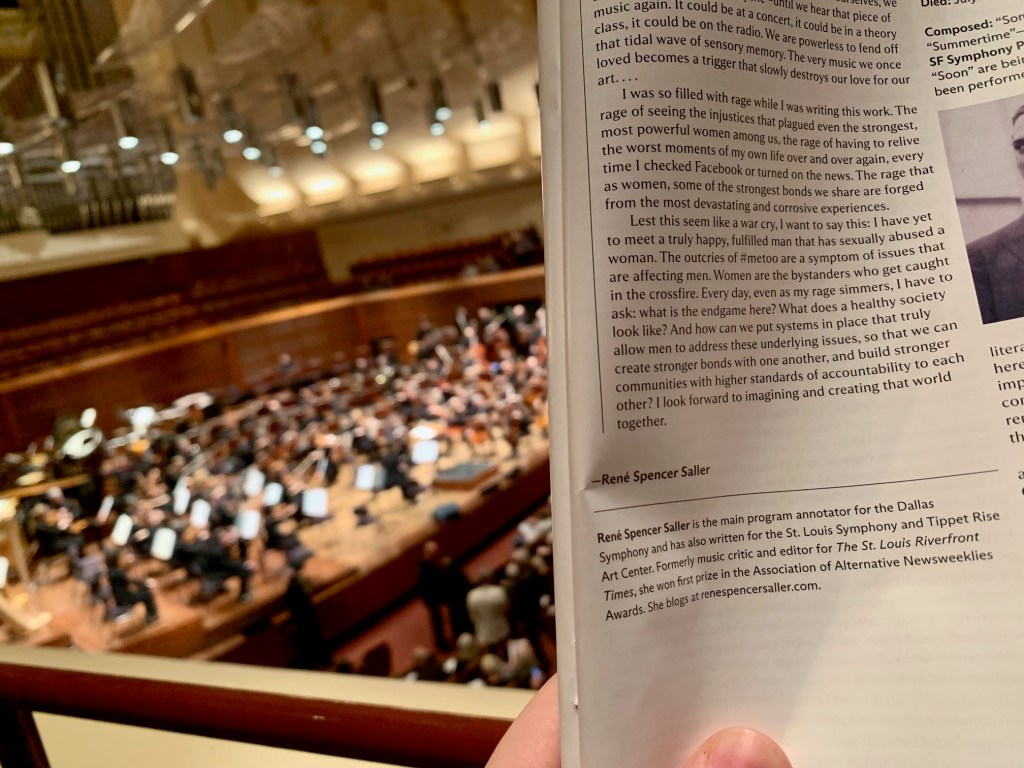

Thanks to my regular longtime freelance gig for the fabulous Dallas Symphony Orchestra, which contains one of the finest concert pipe organs in the country, the Lay Family concert organ at the Meyerson, I have been writing about the vast organ repertoire for years. If nothing else, I’m a diligent researcher, so I know a fair amount about the composers and the histories of the various organs and organ builders (ask me about Aristide Cavaillé-Coll!), and I always interrogate organists if I’m given half a chance, but I never try to conceal the fact that I couldn’t begin to tell you how the whole thing works. In my defense, few people could, apart from organists, and it takes them many years of study to get remotely competent. To play the organ requires a peculiar devotion, even beyond the hours and hours of disciplined practice that musicians who play other instruments routinely log. You need to be one part pianist, one part tap dancer, one part music historian, and one part carpenter-handyman-bricoleur. Strictly speaking, you don’t need to be a skilled improviser, capable of spontaneous feats of complex counterpoint at a moment’s notice, but it helps a lot, insofar as most of the superstar organists can do this in their sleep, especially if they’re trained in the French school—and more on that later, when I finally get around to writing about the Olivier Latry recital at St. Francis de Sales Oratory Catholic church, a short stroll from my home in St. Louis.

I would assume that most proficient organists possess unusually good, maybe even photographic, memories, because how else would they possibly remember where all the stops are, especially if they play numerous organs, all with varying numbers of ranks and manuals? Sure, every piano feels different to a pianist, and every piano has its own personality, its own quirks and distinctive voicings, but pipe organs vary a lot more than pianos do. In fact, I would propose (or wildly speculate) that every pipe organ is unique, because even if two organs were created by the same builder, around the same time, they are still housed in different acoustical structures—the New Cathedral in St. Louis, with its acres of glittering mosaics and its vaulted ceilings, is going to create a very different sonic environment than a concert hall expressly designed for and by audiophiles. As much as I love the organ rep, I am a lazy sod, too busy huffing perfume and stitching my crazy Dolly Parton Crazy Quilt to study the organ with the kind of discipline it demands, so I’m grateful for the many organists I have encountered, both IRL and online, who share their knowledge and passion for the instrument with the legions of total dumbasses like myself. (Please don’t be offended that I’m corraling, or chorale-ing, you into my dumbass cohort—to organists we are all rank amateurs when it comes to their instrument.)

Early on, when I first started covering the organ-recital series at the Meyerson in Dallas, my longtime friend and birthday buddy Jim Utz, a legend in his own right, introduced me to his friend Brent Johnson, the organist at Third Baptist. Through Brent’s late and sadly lamented (by meeeeee) organ recital series at the church, Friday Pipes, which is currently on hiatus, I renewed my passion for pipe organ and began peppering the endlessly patient Brent with dumb questions and comical mispronunciations of German composers’ names (I cringe to recall how I once put a French flair on the name Reger, even though I knew he wasn’t French, simply because I don’t speak German and tried to wing it—one of the perils of being an autodidact who gets most of her information from reading books.) Anyway, via Brent I discovered his YouTube series for the Organ Media Foundation, in which he gives tours of various organs that he visits, discusses with the resident organist, and (I would assume) helps keep in good repair. These videos are absolutely invaluable to me as a researcher because I’m a visual learner, and it helps me to see where the pipes and reeds are located. I also enjoy the interviews with the organists, who know their instruments the way Brent knows his charge at Third Baptist.

Most organists are ambassadors, if not evangelists, for their instruments, which are poorly understood and often unfairly maligned (don’t get me started—no, really, don’t—because my digressions are approaching David Foster Wallace territory, which is no place for anyone besides DFW to be, and likely not even him insofar as he is long dead). But Brent is an especially effective and tireless advocate for his instrument, and one of my favorite discoveries among his good works is the radio program that he produces, The King of Instruments, which airs in the St. Louis area on Classic 107.3, on Sundays at the unreasonable hour of 7:00 a.m CT, and is available online everywhere, at a more humane hour, for which we night owls are grateful. On the website or Soundcloud feed, you can listen to many, many hours of hour-long archived programs, all thoughtfully conceived and organized according to a particular theme or concept. The two hosts, Mark Scholtz and Bill Stein, speak smoothly but never smarmily. They’re authoritative but never pedantic when they introduce these composers, works, performers, and organs. I especially enjoy learning how many ranks and manuals a particular organ has, when it was built, and by whom, because these details aren’t as readily available as, say, the birth and death dates of a specific Baroque contrapuntist. Having listened to a good dozen or more of these archived programs, I find that the hosts provide precisely the correct amount of nerdly detail. Scholtz and Stein leave you feeling cheerful and enlightened, not bored and hopelessly overwhelmed by unrelated factoids.

The best part, of course, is the music. Despite the hundreds of organ annotations and blurbs that I have cranked out over the past decade, The King of Instruments constantly reminds me how little I know and how lightly I have scratched the surface of the repertoire. Even if I stopped listening to Linda Smith and Lloyd Miller and Sexyy Red and Rahsaan Roland Kirk and all the thousands of other, unrelated music makers that I find myself listening to, I wouldn’t be able to hear more than a tiny fraction of all the gazillions of gorgeous fugues and toccatas that have been piling up over the centuries, not to mention all the ones that were improvised on the spot and therefore lost forever, unless they were captured on tape, as many improvisations these days seem to be, fortunately. (Glass-half-empty version: think of all the brilliant Bach improvisations that we’ll never hear simply because they were never recorded—in a perfect world, we might all be trading Bach tapes like the Deadheads do with Jerry Garcia bootlegs.)

The King of Instruments is a highly enjoyable listen if you’re looking for a pleasant soundtrack rather than a college-level lecture enumerating the differences between the French and German schools of organ building. I’m looking for both, as it happens, so I’m content regardless, but I understand if you just want to listen to something while you fold laundry or vacuum the car or respond to emails. I get it because I use music for such purposes myself, and the house of music has many rooms, blah blah blah. It turns out that The King of Instruments suits this function, too, because the show is mostly devoted to music, not to the blah blah blah that I am doing too much of while attempting to sing the praises of this blameless radio program.

One caveat that will be obvious to organists and experienced organ lovers: no matter how great your speakers are, this music simply will not and cannot sound as good as it did when it was being performed, in its native environment. It isn’t possible, so don’t freak out too much, audiophiles. To get that sound, you would need to have a pipe organ in your home (like some lucky Edwardian heiress!), and unless you also occupy a limestone mansion with soaring ceilings, you’re just not going to nail that Notre-Dame de Paris vibe, sorry. Nevertheless, Brent ensures that the sound quality is as good as it can possibly be, especially if you avail yourself of a decent sound system, or better yet headphones, which more closely approximate the immersive effects of hearing this music performed live, on a real pipe organ, although it obviously can’t achieve the full body effects of the live performance.

Despite their limitations, recordings preserve performances by the dead or otherwise unavailable, so they will always have that going for them. I don’t know about you, but counterpoint works a peculiar magic on me. I suck at math (I failed beginning high-school algebra two years in a row), and consequently I would never be able to compose true counterpoint myself, except in the most rudimentary fashion, after tearful hours of trial and error on my tragically underused Knabe parlor grand, whereupon I might come up with something that kindasortamaybe resembles a campsite round, but this is a limitation I cannot correct at my age. Besides, I think my ignorance of the procedure surely contributes to my awe. A Bach fugue is a balm to the ears and brain, exerting a magical organizing effect on my flibbertigibbet consciousness, which typically compels me to mutter Nelly lyrics when I’m supposed to be researching Das Rheingold, or to get sucked down YouTube rabbit holes that invariably lead to Soul Train, my own little Lotos-Land, where I linger for long stretches, propped on beds of amaranth and moly, beneath a heaven dark and holy, etc.

At any rate, if your brain functions or malfunctions like mine, it’s often better to leave the listening choices in expert hands for at least an hourlong chunk or so while you recalibrate. You could pick any episode of The King of Instruments at random, and you would have chosen wisely. I have yet to hear a show that didn’t contain something new and wonderful that I would almost certainly never have heard elsewhere, including many recordings that aren’t even commercially available, recordings that members of the Organ Media Foundation made themselves, with the performers’ permission, of course.

One recent KOI episode (February 11, 2024) was devoted entirely to the organist, composer, and organ consultant Charles Callahan, who died last year on Christmas day. Going into the show, I was completely ignorant of Callahan; one hour later, I understood why they wanted to do a tribute show on this fascinating and talented person. To my delight, the Callahan playlist included a pair of older recordings (2008-ish) that were recorded in the magnificent Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis, which we natives usually call the New Cathedral and which I first had the privilege of touring as a gape-jawed 16-year-old. The organ—and the late Callahan—sound exquisite.

On another, specially expanded recent episode—the last show of 2023, dated December 31—a panel of organist guests join the hosts to discuss their favorite organ works. This was an especially compelling installment for me because I love to hear organists discuss their own experiences learning and then performing a piece—which often means relearning it if they need to play it on a different instrument. “Playing something like this,” one organist says of a favorite toccata, “is the reason we all became organists.”

I’m especially grateful for the shows that focus on the many composers and musicians whose works have been historically underrepresented and underprogrammed, talented people who more than deserve our attention. Many of them are featured on the following first-rate episodes: Women Organists, American Women Composers, European Women Composers, and Black Composers. The good news is that these marginalized artists are getting programmed more frequently, and audiences are increasingly eager to hear music that has been unfairly neglected or deemed unworthy of the canon; the bad news, at least from the annotator’s perspective, is that there is seldom much in the way of reliable information on these works, which means it’s that much easier to make and perpetuate errors. (Ask me how I know, lolsob!) These research challenges make me even more grateful for resources like The King of Instruments. For instance, I thought I knew a fair amount about Florence Price, a brilliant Black American composer who has interested me for a long time and about whom I have written intermittently. Despite this knowledge, I learned a few new facts about her from The King of Instruments and enjoyed a performance that I probably wouldn’t have heard otherwise. I also appreciate the fact that even though the hosts might focus on the artists’ shared race or gender in those aforelinked episodes, they don’t pigeonhole their subjects on the basis of demographic data. For instance, the female composer Fanny Mendelssohn, the prodigiously talented sister of Felix Mendelssohn, is represented in her brother’s episode, which makes sense when you consider how close the two siblings were and how deeply they influenced and complemented each other.

This review is too already too long, or I’d go into more detail about why I consider The King of Instruments to be an invaluable resource for the organ lover. I also maintain that everyone is a potential organ lover. One way to test the truth of that boast is to tune in to The King of Instruments sometime soon. Who knows, it might even inspire you to darken the door of a church in search of your next pipe fix.