I kept thinking I ought to update my blog because I was probably falling behind, but I didn’t bother to check to see when my last update was, and I’m genuinely surprised to learn that it was nearly a month ago. I don’t feel like I have been messing around and slacking off, but the page views don’t lie.

I have been busy writing, but I am not always writing what I ought to be writing, the writing for which I am paid and which my clients have a reasonable expectation of receiving. I have been writing the first draft of a novel that has been marinating in my mind for the past three years or so, maybe longer. I know I am definitely using sections that I wrote back in 2021.

I’m too superstitious to say too much about it, and I don’t want to jinx it by discussing the plot too much before the first draft is complete, but it’s kind of a magical-realist horror novel about identity, art, and motherhood, with a special emphasis on muses and monsters.

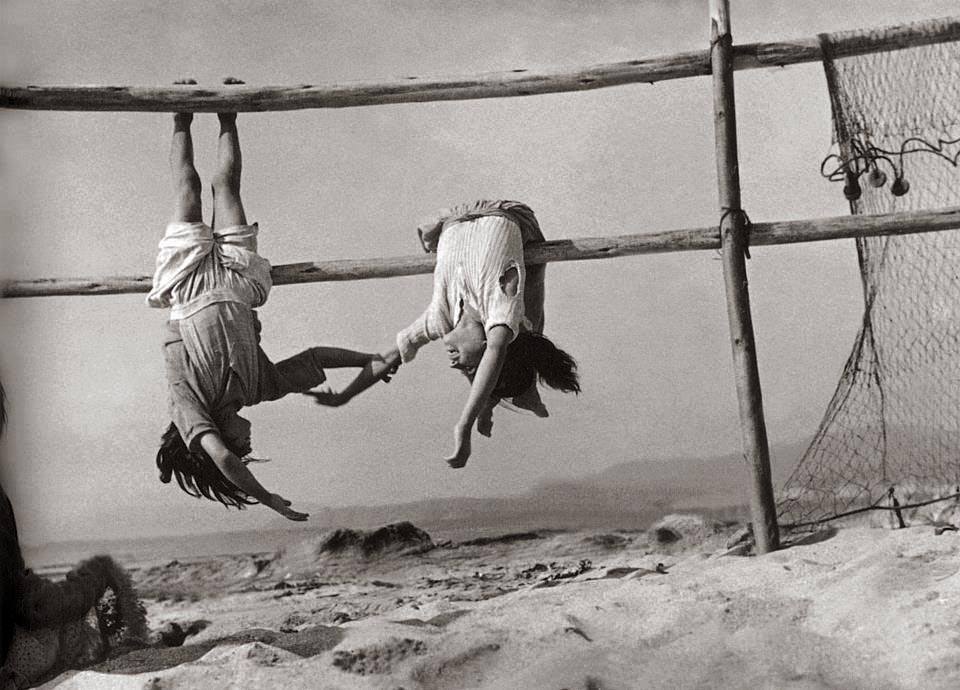

Instead of prattle on too much about something I may very well never finish, I will share some of the photos that are inspiring me for reasons that I hope will be clear to at least a few people someday. As a lifelong compulsive reader, I have always suspected that there are far more great novels out there than I will ever be able to read, which is a huge disincentive to write, because why contribute to the glut, right? Most people don’t read anything close to the 70 or so novels that I’ll probably end up reading this year, and believe me I don’t make a dent in my Daunting Queue. I could show you my Goodreads stats, but why bother? We all know that the world needs another novel like it needs another novel coronavirus.

And yet why not finish it, even if it never gets published? I already know it’s not going to be another Moby Dick, and that manuscript was a total flop in Melville’s lifetime, so who can say what will happen? But if I never finish writing it, I’ll for sure never know.

All the subjects in these photos are somehow significant in the novel, but it is not a historical novel. And that’s the last thing I’ll say about it because I hate enigmatic posts and related forms of rhetorical coyness!

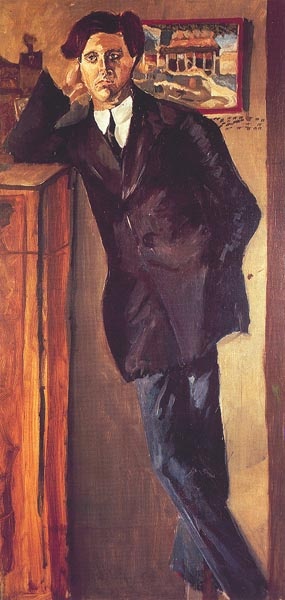

Many of these photos are of Manon Gropius, whose Wikipedia entry lists her occupation as Muse.

Some gig, huh? Berg called her an angel, and Canetti called her a gazelle, and her polarizing mother pawned her off on Austrofascists. Kid never stood a chance.

Oh, and just to keep this connected to my regular writing career, here are some program notes that I wrote about Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto, which he wrote in memory of Manon, whom he called an angel.

A Double Requiem

Berg’s Violin Concerto, his last completed composition and arguably his most beloved, serves both as an elegy for Manon Gropius, the 18-year-old girl that he had loved like a surrogate daughter, and as a requiem for himself. Indeed, he died shortly after finishing it. According to his wife, he worked at a frantic pace, as if he knew his days were numbered. “I cannot stop,” he explained when she begged him to slow down. “I do not have time.”

In 1904, when Berg was 19 years old, his older brother brought a stack of his lieder to Arnold Schoenberg, who had placed a newspaper ad seeking composition students. Although Berg’s family was too poor to pay for lessons, Schoenberg took him on anyway. Between 1901 and 1908, Berg wrote approximately 150 songs and other vocal works. After the dismal failure of his Altenberg Lieder in 1912, he stopped writing songs. Until his sudden, squalid death at age 50, from an infected insect bite, Berg focused almost exclusively on two operas: Wozzeck, which he completed in 1922, and Lulu, which remained unfinished when he died, on Christmas Eve, 1935.

Commissioned by the American violinist Louis Krasner, the Violin Concerto was Berg’s last completed work. When Krasner first approached Berg with the proposal, the composer was busy with Lulu and reluctant to crank out a glitzy showpiece. “You know that is not my kind of music,” he told Krasner. He needed money badly, however, so he eventually relented. On April 22, two months after he had accepted Krasner’s commission, he learned that Manon Gropius, the beautiful 18-year-old daughter of Alma Mahler (Gustav’s widow) and the architect Walter Gropius, had succumbed to poliomyelitis. Inspired by the death of a girl that he “loved as if she were his own child, from the beginning of her life,” as her mother phrased it, Berg began to work in earnest. He composed most of the Violin Concerto at his country home, Waldhaus, in Velden am Wörthersee, in the Carinthia region of Austria.

In early June, Berg invited Krasner to join him and his wife, Helene, at Waldhaus. The two men played through the first part of the concerto together, hashing out the solo part. As Berg worked on the second half of the concerto, he asked Krasner to improvise in another room. When the violinist would tire, after playing nonstop for hours on end, Berg would suddenly appear and urge him to continue. By July 15, the score was more or less complete; the orchestration was finished less than one month later. “I have never worked harder in my life,” Berg declared, “and what’s more, the work gave me increasing pleasure.” After obtaining permission from Alma Mahler, he dedicated the Violin Concerto “to the memory of an angel.”

Berg never got the chance to review and correct the published score, and he died before the premiere could take place. Krasner performed the solo role on April 19, 1936, at the International Society for Contemporary Music Festival in Barcelona.

A Closer Listen

Cast in two large movements instead of the conventional three, Berg’s Violin Concerto can be further divided into four parts. The first movement comprises an Andante section and a longer Allegretto section. The second movement begins with an Allegro section and concludes with a substantial Adagio. According to many commentators, the first movement represents life, the second death and transfiguration. In the first movement, Berg quotes from a Carinthian folksong, a rustic Ländler that some scholars interpret as a wistful allusion to Marie “Mizzi” Scheucl, the servant girl who bore his illegitimate daughter in 1902, when he was 17 years old.

Early in the summer of 1935, Berg asked his research assistant, Willi Reich, to send him some of Bach’s cantatas. In the last part of the second movement, Berg incorporates a series of variations on “Es ist genug!” (“It is finished!”), using some of Bach’s original harmonies. The chorale’s melody begins with the last four notes of Berg’s tone row: B, C-sharp, E-flat, and F. Because it contains all twelve notes of the chromatic scale, the tone row is the foundation for twelve-tone composition, a formal procedure that Schoenberg developed and taught to Berg. But Berg’s series of notes also lends itself to a looser, more tonal mode of expression, which accounts for the Violin Concerto’s considerable emotive power.

Copyright 2018 by René Spencer Saller

A bit of bonus content for the true fans: