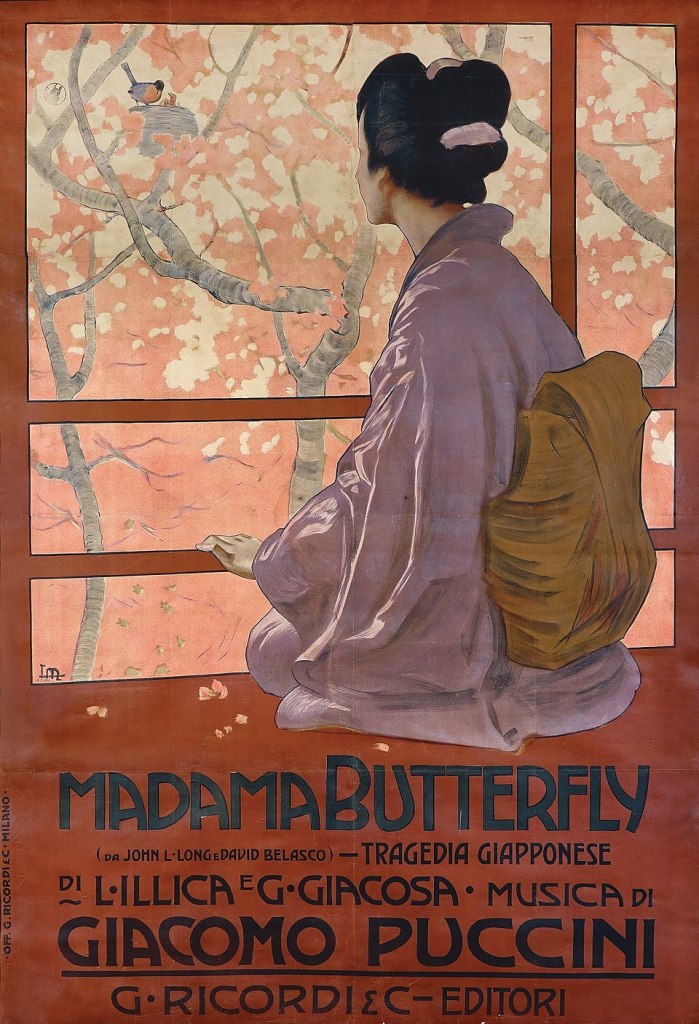

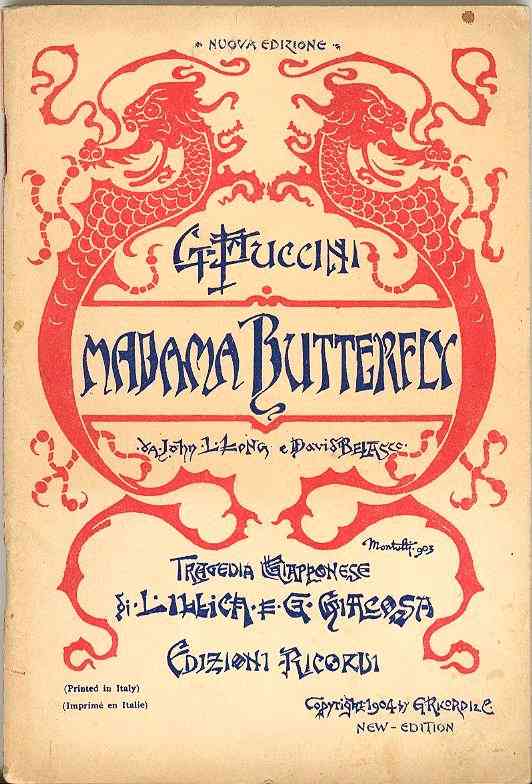

I wrote about Puccini’s Madama Butterfly recently for the Dallas Symphony, which performed the entire opera as a semi-staged production. The artwork is all from Wikipedia Commons.

Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924): Madama Butterfly (complete)

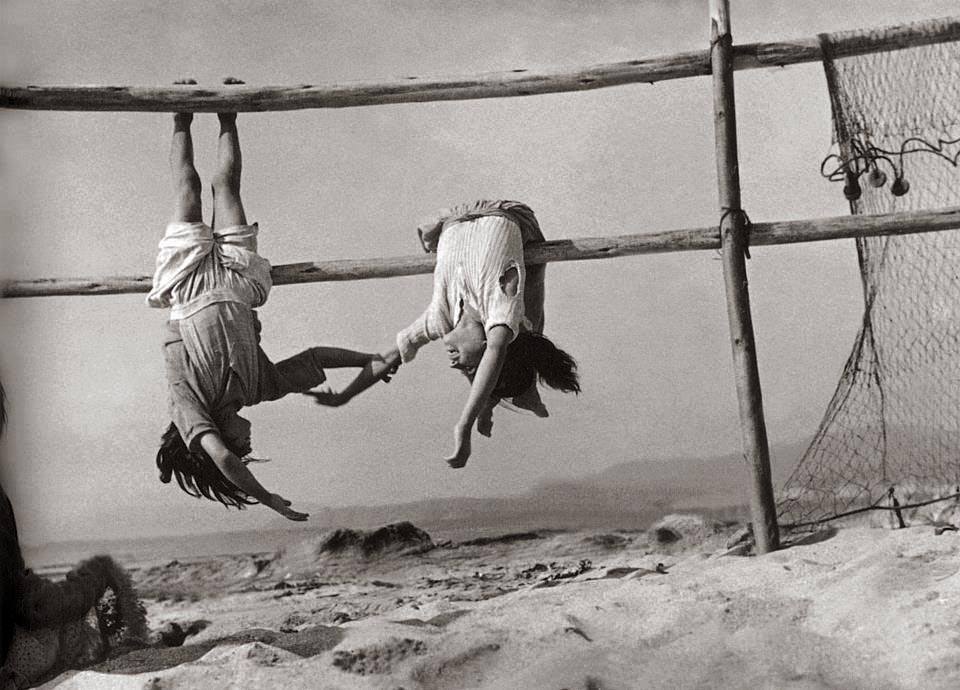

In Madama Butterfly, as in so many Italian operas, a beautiful and blameless victim suffers at the hands of her selfish exploiters. Her death, foretold from the start, is a genre requirement, a device that delivers her from evil once she unleashes her climactic closing aria. Seduced and abandoned, the soprano is sacrificed so that we can grieve her. The engine of our collective catharsis, she lets us rage against the cruelty of a world where impoverished children are sold to men who use them like toys and discard them like trash. Is the misery of the teenage geisha sold to Lt. Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton substantially different from any redacted Epstein victim’s pain? If the details vary, the moral remains grimly consistent. Madama Butterfly is a century old, but its world is our world.

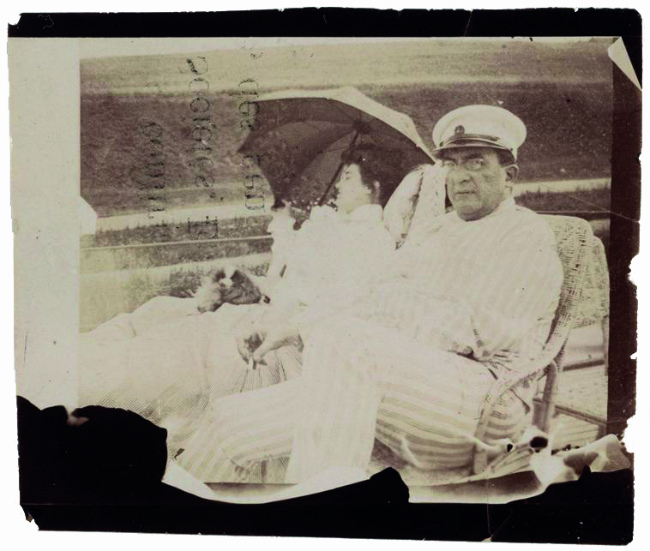

Despite his status as the most successful opera composer of the 20th century, Puccini once seemed fated to play the organ in his native Lucca. He was descended from a 200-year line of cathedral organists, and he showed early promise on the instrument. But in 1876, when he was 17, he walked 15 miles, from Lucca to Pisa, to attend a performance of Aida. Just like that, Verdi’s darkly alluring spectacle made the young man forsake church music for the stage. In 1880 he enrolled at the Milan Conservatory, Verdi’s alma mater.

Like Verdi, Puccini loved literature, particularly plays, a frequent source of material for his operas. In 1900 he attended a London production of a one-act tragedy called Madama Butterfly by the New York dramatist David Belasco. Belasco, known for his gritty realism, adapted the play from an 1898 magazine story by the American lawyer and writer John Luther Long, who in turn based the plot on a supposedly true story recounted by his missionary sister in Japan. (In 1927 Long’s New York Times obituary quoted his own description of himself: “a sentimentalist, and a feminist, and proud of it.”)

Deeply moved by the heroine’s plight, and intrigued by the creative possibilities associated with the setting, Puccini began sketching out an eponymous opera. He logged countless hours of research, all in the service of dramatizing the lead characters’ tragic clash of cultures. He wanted his score to reflect the singers’ essential personalities, the singular ways they provoke and misunderstand one another. He reunited with the librettists Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica, who collaborated on his previous hits La bohème and Tosca, and the first version of Madama Butterfly debuted on February 17, 1904, at La Scala, in Milan.

Unfortunately, this Butterfly fluttered briefly and failed to take flight. The audience jeered, bellowed, and disrupted the arias with crude animal noises. The star soprano collapsed in tears, unable to distinguish her cues through the din. Never mind that the chaos was mostly engineered by two of his rivals: Puccini was bitterly disappointed by the early response. He never doubted the quality of his score, however. “Those cannibals didn’t listen to a single note,” he complained to a friend. “What an appalling orgy of lunatics, drunk on hate! But my Butterfly remains as it is: the most heartfelt and evocative opera I have ever conceived!”

Even so, he withdrew it from production. He revised the opera at least five times, testing each iteration in select international venues, until 1907, when he was finally satisfied.

Settling on a final form for Madama Butterfly must have come as a relief to the composer, who had recently experienced a barrage of momentous life changes. In 1903 a serious car accident left him unable to walk for several months, and early in his recovery he was diagnosed with diabetes. A year later, one bright spot: his long-anticipated marriage to Elvira Gemignani, the mother of his son. The couple had been forced to postpone their wedding until the death of her first husband, who never granted her a divorce. In 1906, months before the final version of Madama Butterfly was staged, his valued collaborator and librettist Giacosa committed suicide at age 58.

A Closer Listen

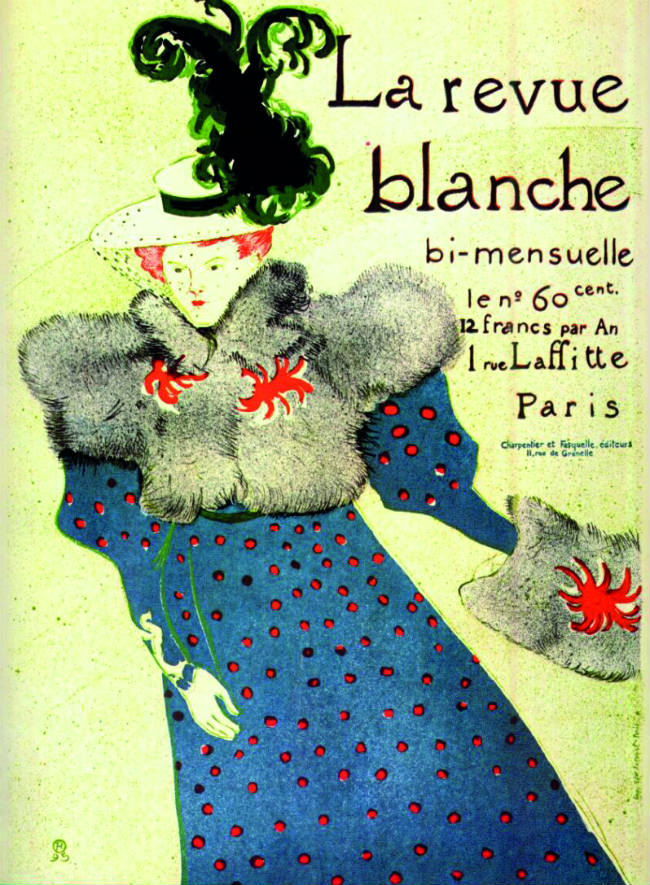

Puccini may have been capitalizing on the japonisme craze that consumed late 19th-century European (and British and American) culture, but that doesn’t detract from the originality of the execution. Unlike so many of his fellow cultural appropriators, he approached his topic with humility and respect, researching every detail to the best of his abilities, from the colors of the flags to the timbres of the folk instruments and the cadences of the local dialects. To simulate the sound of his heroine’s native music, he asked a neighbor, Hisako Oyama, the wife of the Japanese ambassador to Italy, to sing traditional songs for him. He interviewed a musicologist about the finer points of meter and pitch, met with the Japanese actress Sadayakko when she toured Milan, and took in several performances by the Imperial Japanese Theatrical Company. In early 1902 Puccini wrote to Illica about the field research that he was planning to do in the interest of authenticity: “I’ve now embarked for Japan and will do my best to portray it, but more than publications on social and material culture, I need some notes of popular music.”

To depict Butterfly and her culture, Puccini chose melodies derived from the pentatonic scale and other non–Western-sounding modalities. This Japanese-inspired music deepens and differentiates her character and also serves as aural stage design. The instrumental passages range from transparent watercolors to vivid pen-and-ink narratives, as richly detailed as a master’s landscape. To set up maximal contrast, the opera begins with a concise prelude in the form of a fugue, arguably the most Western of procedures. As exacting as a math puzzle, the fugue formalizes the union of different voices, weaving together seemingly disparate components to create new contrapuntal patterns. But the fugue is a rigorous and unforgiving form, one that dominates as it explores, whereas Butterfly values the natural world, the spontaneous and heartfelt gesture.

Any listener who notices this dichotomy, or even registers it subconsciously, understands that poor Butterfly is doomed before she’s midway through her first song. Some dumb and undeserving, clumsy-pawed clod is going to smear all the fine iridescent powder off her wings, leaving her flightless, helpless, crawling around in the dirt. But knowing that her pure and tender love is misplaced doesn’t detract from its power. Puccini makes us adore her before she even appears onstage: as with so many of his greatest heroines, her glorious introductory aria precedes her. Her love is so wild, ardent, and free that we fool ourselves into hoping, against our better judgment, that she can convert a callow playboy into a reliable husband.

Puccini created an equally distinctive musical language to convey Pinkerton’s national identity, his endless appetites and supreme Yankee entitlement. Careful listeners will detect traces of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in the orchestral introduction to his first aria, in which he boasts about his many global conquests. Not yet the national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner” was at that time widely associated with the U.S. Navy, and therefore a natural choice for Pinkerton.

Butterfly’s musical vernacular evolves as the action unfolds: in Act I, thanks in part to the strategic accompaniment of a harp, she sounds significantly more Japanese than she does in Act II, which takes place three years into her self-styled metamorphosis from Butterfly to Mrs. Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton. By the end of Act III, when she sings her exquisite suicide aria, she briefly re-assumes her Japanese identity, as if to resurrect the unspoiled girl from the opening act.

Synopsis

Act I: In imperial Nagasaki, at the turn of the 20th century, U.S. Navy Lieutenant Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton reviews his living arrangements with Goro, a local landlord and marriage broker. When the American consul, Sharpless, shows up, Pinkerton gloats about the terms of his lease (999 years, with the option to leave whenever he wants) and the terms of his impending marriage (valid only until he decides to exchange her for a “real” wife). Pinkerton’s boorishness makes Sharpless uneasy, and he warns the lusty lieutenant to be careful of the girl’s feelings.

Pinkerton is presented with the 15-year-old geisha whom he recently bought: an enchantingly sincere girl named Butterfly, or Cio-Cio-San, who, inexplicably, has fallen instantly, deeply, and permanently in love with him. Although she comes from noble stock, her family fell into poverty after her father committed suicide at the emperor’s request. She proudly announces that she has changed her religion: as a newly minted American wife, she intends to worship only the American god. Toward the end of the simple wedding ceremony, the powerful priest Bonze, Butterfly’s uncle, shows up and curses the bride for her treachery. Pinkerton orders Butterfly’s relatives to leave, and they all denounce her as they depart. After Pinkerton caresses and consoles Butterfly, they sing a long and passionate love duet.

Act II

Three years have elapsed, and Pinkerton is long gone. Butterfly and Suzuki are nearly destitute. When the long-suffering Suzuki prays to the gods for grocery money, Butterfly accuses her of trusting “lazy Japanese gods” instead of her husband, who left soon after their wedding but promised to return in spring. The consul Sharpless arrives with a break-up letter from Pinkerton in hand, but before he can complete the painful task, Goro appears with the wealthy Prince Yamadori, who hopes to procure Butterfly for himself. She serves the pair tea but rebuffs them, insisting that her beloved American husband would never betray her.

After the Japanese men leave, Sharpless tries once again to read her the letter and tactfully suggests that she might want to reconsider Yamadori’s proposition. By way of response, she introduces Sharpless to her blue-eyed toddler son, explaining that his current name is Sorrow; she plans to change it to Joy when his father returns. She makes Sharpless promise to tell Pinkerton about their child, and he agrees. After a cannon shot sounds in the harbor, Butterfly and Suzuki use a telescope to read the name of the ship, rejoicing when they confirm that it’s Pinkerton’s. They adorn the house in fragrant blossoms from the garden. As night descends, Butterfly, Suzuki, and little Sorrow await Pinkerton’s return to the distant strains of the sailors’ monotonous humming.

Act III

In the morning Suzuki urges Butterfly and Sorrow to retire to their chambers. While mother and son rest inside, Suzuki greets Sharpless, who is accompanied by Pinkerton and his new American wife, Kate, who wants to adopt Butterfly’s child and raise him as her own. Older and wiser than her mistress, Suzuki is heartbroken but unsurprised. She promises to discuss the offer with Butterfly after Pinkerton admits that he is too weak to confront her himself. He takes a moment to reminisce about their time together, then flees the scene like a coward.

Hearing his voice from inside the house, Butterfly rushes out to embrace him. Instead, she finds Kate and intuitively understands who she is and what she wants. Butterfly tearfully agrees to hand over her son, but only to Pinkerton directly. In the meantime, she dons her wedding kimono and takes out the ceremonial dagger that her father used to absolve his shame and restore his honor. But before Butterfly can reenact the gruesome ritual, her son appears at her side. She embraces him one last time, covers his eyes with a blindfold, and assures him that she is sacrificing herself to ensure his future happiness. After she plunges the blade into her body, the last sound she hears is the approaching voice of Pinkerton, uselessly calling her name.

Copyright 2026 by René Spencer Saller. Originally published by the Dallas Symphony. All rights reserved.