As regular readers of this lamentably sporadic blog know, I usually write program notes for specific concerts. But one of my freelance clients, the estimable San Francisco Symphony, recently asked me to write a couple of features this concert season, too. In the alt-weekly olden days of yore, we used to refer to such essays as “thinkpieces.” In fact, I was often accused, by my superiors, of writing too many of them. But this time one was actually commissioned from me, by one of my wonderful editors, with my only constraints being that the essay should focus on the connections between Beethoven and Mozart. I thought about Harold Bloom’s book The Anxiety of Influence, which I read a million years ago in graduate school, and I also thought about the college class I took my senior year, in which Bloom’s book was assigned. That class was called Literary Friendships, taught by a brilliant professor named Ross Borden, who focused on Coleridge/Wordsworth, Byron/Shelley (with a side of Keats somewhere?), and Eliot/Pound. At any rate, I loved that class, and I loved thinking about the ways in which relationships can both form and deform.

I’m going to include the link to the essay here (the artwork is so pretty!), but I’m also going to cut and paste the essay in the body of this blog entry because all the links I inserted in previous years are dead or broken, and I have never rebuilt them, not that I would have any idea how to go about doing such a thing.

Becoming Beethoven

by René Spencer Saller

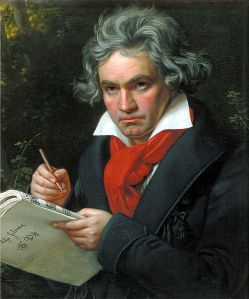

After hearing Mozart’s C Minor Concerto for the first time, Beethoven supposedly exclaimed to a colleague, “We shall never be able to do anything like that!”

For many composers—and artists in general—the line between legacy and burden is blurry at best. What happens when a creative influence doesn’t inspire so much as inhibit? Harold Bloom wrote two books on the topic, The Anxiety of Influence and A Map of Misreading. In them the late literary theorist argued that the strongest poets are the ones who misread their fearsome forebears, usually as a subconscious defense mechanism against the ego-corroding force of influence. This productive misunderstanding helps the strongest, most original poets protect their developing egos and reclaim their creative mojo. Replace “poet” with “composer,” and Bloom’s theory works equally well.

Bloom reframes the issue of influence in Freudian terms, but you don’t need to review your Psych 101 notes to understand the related concept of ambivalence. Most of us know what it feels like to admire someone who makes us feel inferior by comparison—for me, if you must know, it’s Jan Swafford and the late Michael Steinberg—so we get why the ego might develop defense strategies against this profuse admiration. Kill your idols, as the ’80s punk slogan goes. It’s never quite that easy, alas. Your idols might be dead already.

As a teenager in his native Bonn, Beethoven was urged by his patron Count Waldstein to make a pilgrimage to Vienna and “receive the spirit of Mozart at Haydn’s hands.” Although he dutifully complied, the pressure made him queasy. On the one hand, he wanted to enter the pantheon; on the other hand, he needed to assert his independence. Just as Beethoven’s looming presence would both inspire and inhibit his successors— “Who can do anything after Beethoven?” Schubert famously griped—Mozart provoked a similar ambivalence in Beethoven.

Although Beethoven pored over Mozart’s scores from early adolescence and would later study with Mozart’s teacher and champion, Joseph Haydn, no one knows whether Beethoven and Mozart actually met. Swafford, who wrote comprehensive biographies of both composers, believes that it’s possible, although most of their reported exchanges seem to be fabricated. Beethoven did take in some Mozart performances, both in Bonn and Vienna. But regardless of whether theirs was a literal or a purely parasocial relationship, the connection started during Beethoven’s childhood, when his drunken wastrel of a father tried to transform himself from a small-time music instructor into Leopold Mozart, the consummate Stage Dad, while positioning the young Beethoven, who was about 14 years Mozart’s junior, as the hot new talent. Given expert guidance and instruction, the child might have been capable of taking on the prodigy circuit, but his father lacked Leopold’s entrepreneurial drive and discipline. Beethoven’s father seldom saw anything through, aside from the brutal beatings that he regularly inflicted on his children. He was a burden, not a provider.

Beethoven might not have been swanning around the continent and hobnobbing with royalty as a child and teenager, but he was a different kind of prodigy. Unlike Mozart, who mostly trained on a harpsichord rather than a pianoforte, he was primarily a pianist—and he made it his business to investigate all the recent developments in acoustic design and keyboard expansion, often complaining in letters about the limitations imposed by his current models. As a lifelong virtuoso, Mozart took an interest in the instruments he played and owned, but he died before many significant innovations came about.

Beethoven may have seen the rapidly evolving pianoforte as one way out from under the burden of Mozart’s influence. In 1809, the year Haydn died, Beethoven published a new and blindingly difficult first-movement cadenza for his Second Piano Concerto. This new cadenza, which fully exploited the wider range of cutting-edge piano design, was conceived for an instrument that literally did not exist in Mozart and Haydn’s day.

Beethoven understood that he needed to sound as Beethovenian as Mozart sounded Mozartian. Paradoxically, he became most distinctively himself when he learned so much Mozart that he could channel him almost intuitively, improvise on his themes, lift his harmonic shifts, quote lines from his operas—the one form where Beethoven comes up short. (Don’t fight me, Fidelio fans: I’m confident that Beethoven, who adored Die Zauberflöte, would agree.)

If the Bloomian or Freudian interpretation feels needlessly combative to you, you’re not alone. Some of us perceive creative influence as a source of joy, a way to converse and commune with formative paternal and (not that Bloom ever fully acknowledged them) maternal figures. Often the dynamic of influence seems less like a competition designed to vanquish and subjugate the problematic precursor and more like a posthumous collaboration. The most loving response to a work of art, or a sunset, or a child, or an ailing parent, is close attention. When we focus fully on another human being or on something created by another human being—large language models need not apply!—we escape the constraints of consciousness and time. Often, as Beethoven found in Mozart, we discover an ally, not an authority figure or a rival. Instead of punishment and endless one-upmanship, this form of influence offers sustenance and support.

We don’t need to kill our idols, or even maim or disfigure them. We can follow the lead of Beethoven, who undercut the occasional snippy comment—he allegedly told his student Carl Czerny that Mozart’s playing was fine but choppy, lacking any legato—with the only tribute he cared about, the musical kind. His many quotations from Mozart scores aren’t the main reason that music writers invariably refer to Beethoven’s Mozartian tendencies. Beethoven immersed himself so completely in Mozart’s sound world that he could recreate it in his own singular language. This degree of devotion is best described as love.

On a sketch in C minor from 1790, the year before Mozart’s premature death, Beethoven dashed off a note, to himself and to posterity: “This entire passage has been [inadvertently] stolen from the Mozart Symphony in C [“Linz”]. He then made a few minor adjustments to the passage before signing it “Beethoven himself.”

Whether Beethoven “misread” Mozart to enact his Mozartian magic is immaterial. For almost his entire life he was pitted against his near-contemporary, and people continued to compare them long after their respective deaths. We compulsively play the same dumb rhetorical games with different artificial binaries—Beatles vs. Stones, Kendrick vs. Drake, boxers vs. briefs—as if a fondness for one thing precludes appreciation of the other. Declaring our allegiance to Mozart instead of Beethoven, or vice versa, narrows our range of experience and deprives us of pleasure.

I say this as someone who recalls, with the hideous clarity reserved for my cringiest takes, grandly announcing at a dinner party that I didn’t much care for Mozart and much preferred Beethoven. Blissfully untroubled by my non sequitur and probably visibly drunk, I blabbered on idiotically in this vein to my then-boyfriend’s sister-in-law, who happened to play flute in a major American orchestra. Like most Mozart fans, she was merciful and unpretentious, cheerfully steering the conversation away from my indefensible opinion.

In his critical reappraisal of Beethoven, the late musicologist Richard Taruskin lamented what he called the “newly sacralized view of art” and blamed Beethoven for turning concert halls into museums or temples. He was right to question the Romantic myths surrounding Beethoven’s life and career, the overwhelming tendency to present his struggles as heroic, his suffering as unique and transcendent. But Taruskin also felt that Beethoven’s influence stifled his successors more than it freed them to pursue their own creative paths. Through no fault of his own, the fallible human being became a godlike authority, a scary dad, a mentor-cum-tormentor of future generations.

If you were expecting a sassy Taruskinesque takedown, sorry to disappoint. Although we do Mozart and Beethoven no favors when we turn them into distant unknowable gods, we also gain nothing by trashing them. Besides, if there’s anything sillier than worshiping the dead, it’s fighting the dead, or even defending them. The best will survive our blather. After all, they survived one another.

Copyright 2026 by René Spencer Saller. (Originally published by the San Francisco Symphony)